SAN DIEGO — The decades-old agreements that outline water rights to the Colorado River basin are leading to an impasse on an issue affecting millions of people in the American Southwest.

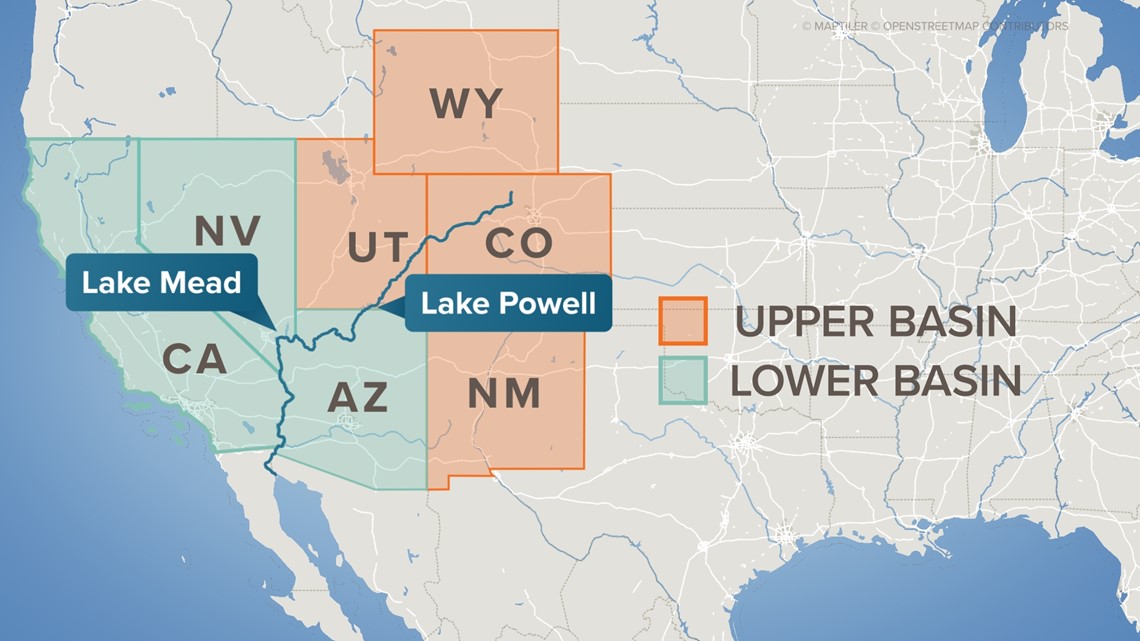

On Jan. 31, the seven states that draw water from the basin had to come up with a plan to voluntarily cut back on using water from the basin. Six states — Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming — agreed on one proposal. But California, which is the state the uses the most water, rejected that plan and submitted its own.

"I think that the proposals of the six states and the proposals of California are nothing more than preliminary posture," said Craig Kessler, Chair of the Coachella Valley Water District Golf and Water Task Force. "They're positioning themselves for a what's going to be a serious negotiation in the immediate future."

The January deadline had been set by the federal government because of the severe drought affecting the Colorado River Basin and both Lake Mead and Lake Powell — the two largest reservoirs in the country. The goal is for states to figure out a way to use between 15% and 30% less water.

History

Back in 1922, the Colorado River Compact agreement divvied up water rights to the river basin among seven states. Water from the basin has served as a crucial lifeline to these states.

But no state has benefitted as much from this resource as California.

In fact, Kessler says the Colorado River helped support California's transformation into the socioeconomic powerhouse that it is today. California is the most populous and biggest agriculture-producing state in the country. That is a key reason why California rejected the other states' plan.

"The other six states are going for an equitable distribution," Kessler said. "If you look at the populations of Nevada and California to suggest they should be equitable... obviously 40 million persons have more water needs and the largest agricultural state in the union has more water needs than Nevada."

The way in which California uses this water has evolved over time.

According to Dan Denham, deputy general manger of San Diego County Water Authority, California was overusing its allotment to water from the Colorado River in the 1990s.

"California had to go on a water diet," Denham said. "It was a tough thing to do politically and financially and environmentally."

This led to the Quantification Settlement Agreement in 2003, which involved San Diego County Water Authority and other local, state and federal agencies. The Water Authority says this agreement helped reduce California's reliance on the river "through voluntary agriculture-to-urban water transfers and other water supply programs." The agreement also holds the parties involved to uphold standards that promote public and environmental health.

"California voluntarily stepped forward when it didn't have to," Kessler said. "The Quantification Settlement Agreement of 2003 permanently ceded quite a bit of the capacity and [California] has since ramped up even more infrastructure projects to accommodate that."

California's plan

Now the Colorado River Board of California, which represents the state in negotiations, is suggesting a new plan.

Instead of adjusting for water lost due to evaporation and transportation, a proposal from the other states that would seriously impact California, the board's plan suggests reducing the amount of water taken out of Lake Mead. It is located on the Arizona-Nevada border and those two states would suffer the biggest reductions.

"In the letter there's a reference to perhaps Arizona doing a quantification settlement of its own," Denham said.

Arizona is one of the states that had previously ceded some water rights in the 1960s to build the Central Arizona Project, a canal that supplies water to more than 80% of the state's population.

One argument representing a core part of this debate is focused on the "Law of the River." That refers to a series of agreements and court rulings that have created the current water rights structure that strongly favors California.

"The federal government, which brought this together and has some say in this, has to figure out a way to bring those states together to do it," Kessler said." Because the reality is that the federal government can't override the Law of the River."

The federal government doesn't have to step in just yet. Negotiations are still ongoing, and the states involved will continue meeting to try and come to a common ground on what voluntary reductions they can make.

As these states continue to grow larger and more developed, they will also develop a greater need for water. Each state is trying to set themselves up in the best possible position to lay claim to these water rights. But litigation would be a last resort.

"I think it's in nobody's interest to end up in in litigation. It's not in the interest of the states, it's certainly not in the interest of the federal government and it's not in the interest of the 40 million persons who depend upon the Colorado River," Kessler said. "They will come to an agreement because they have to."

What's next?

Denham says although more than half of the water used in San Diego County comes from the Colorado River, there is no immediate threat.

"Right now, there would be no impact to the residents of San Diego County," Denham said.

Since California has some of the strongest legal claims to water rights from the Colorado River, cuts would first impact other states, like Arizona and Nevada. However, if more serious cuts are mandated by the Secretary of the Interior, this could impact the Metropolitan Water District, which serves Southern California and parts of Los Angeles and San Diego. If those cuts were to follow the "Law of the River," they would first hit urban areas rather than agricultural developments.

"Of the 4.4 million acre-feet that we have as a state from the Colorado River, the vast majority of that — more than 3.5 million acre-feet is for farming. 550,000 acre-feet of that water is reserved for metropolitan — that’s urban use," Denham said. "And that’s the portion of water that is of the lowest priority on the system."

But Denham says San Diego's connection to the Colorado River water is tied to longstanding senior water rights with the Imperial Valley. Thus, cuts would first hit the Metropolitan Water District rather than the Water Authority.

In the meantime, San Diego County is pursuing numerous infrastructure projects to reduce the threat of a water crisis. That includes the Carlsbad Desalination Plant, which opened in 2015 and provides 56,000 acre-feet of water that is drought proof. Developing more recycled water programs will also play a key role in providing long-term stability for the region.

"Long-term planning is desperately needed to be injected into the conversation rather than just simply short-term fixes," Denham said. "We need to start thinking about how to plan for those projects to be online when the next drought hits — if we're able to get passed this one."

Watch Related: Water conservation is critical in San Diego County as Colorado River declines (Aug 17, 2022)