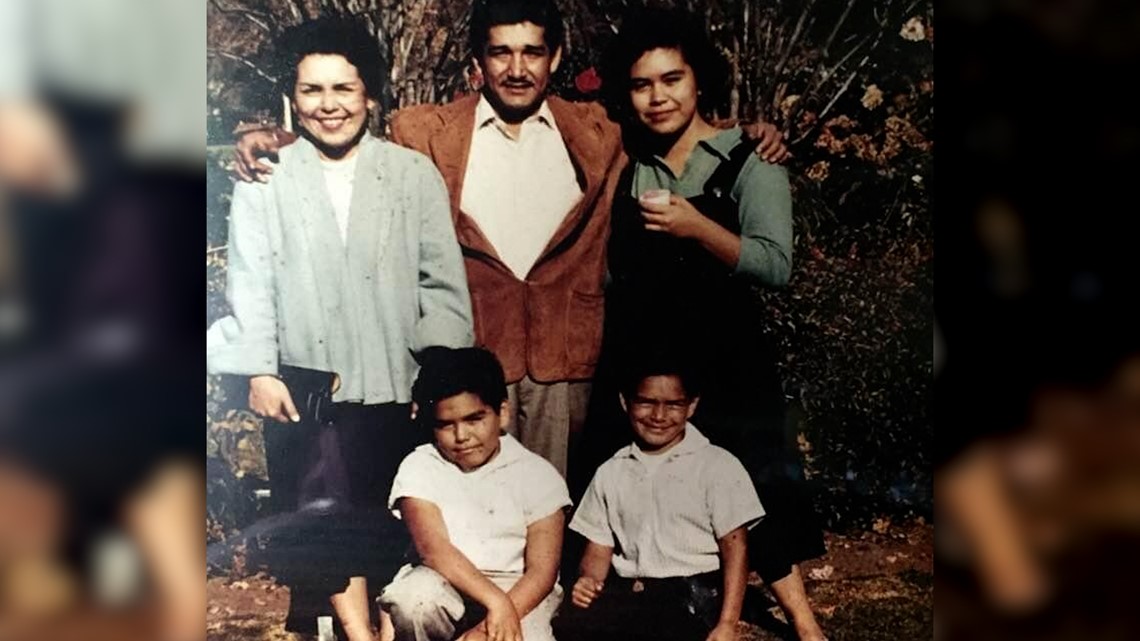

SACRAMENTO, California — David Rasul, “tortilla bred and fed in Sacramento,” was born into a Mexican American, working-class family in 1947. Little did he know he’d be part of history.

Rasul joined the largest civil rights movement by Mexican Americans. The Chicano Movement, also known as El Movimiento, advocated en masse for political, social and economic equality for Mexican Americans starting in 1965 until 1980.

Now, he’s one of the Chicano elders committed to preserving their history. He helped create the nation’s largest Chicano oral history collection housed at Sacramento State’s Library.

The struggles David Rasul faced growing up

Rasul is a Dean of Counseling Emeritus at Sacramento City College, a Vietnam veteran, a civil rights activist and a pillar in the community. Before all that, he was a young boy born to cannery workers growing up in a South Sacramento barrio, or neighborhood.

He understood the importance of hard work from an early age. He became a janitor as a teenager to help pay for his private education at Christian Brothers High School. He also took on side jobs and after graduation became one of the first Chicano beer salesmen in Sacramento for Budweiser.

Tears start to roll down his face as he talks about his past.

“I still get a little lump in my throat thinking about the things that I went through,” said Rasul.

He recalls a Christian brother, a religious leader, from his high school telling him about a lumber company looking for some extra help. After inquiring about the job, the supervisor quickly shut him down. Rasul didn’t think much of it.

“On Monday, when I was back at school, I told the brother what had happened and he says, ‘Come into my office.’ So I went into his office and he called the guy. He started not yelling but using a stern voice and then after he hung up, he turned to me and said, ‘David, be prepared because of your skin color. You’re going to encounter a lot of this.’”

This was one of many instances where Rasul would experience racism for being a brown-skinned Mexican American man.

After his first week working for Budweiser, his supervisor told him a handful of businesses banned Rasul from coming back because of his ethnic background.

“You can only take discrimination, racism and oppression for so long,” said Rasul. “I'm just a little microcosm of the whole thing, but that happened to a lot of people all over [the] United States and I think the Chicano Movement was born out of that, that ‘Hey, we can't take any more of this.'”

Sacramento’s role in the Chicano Movement

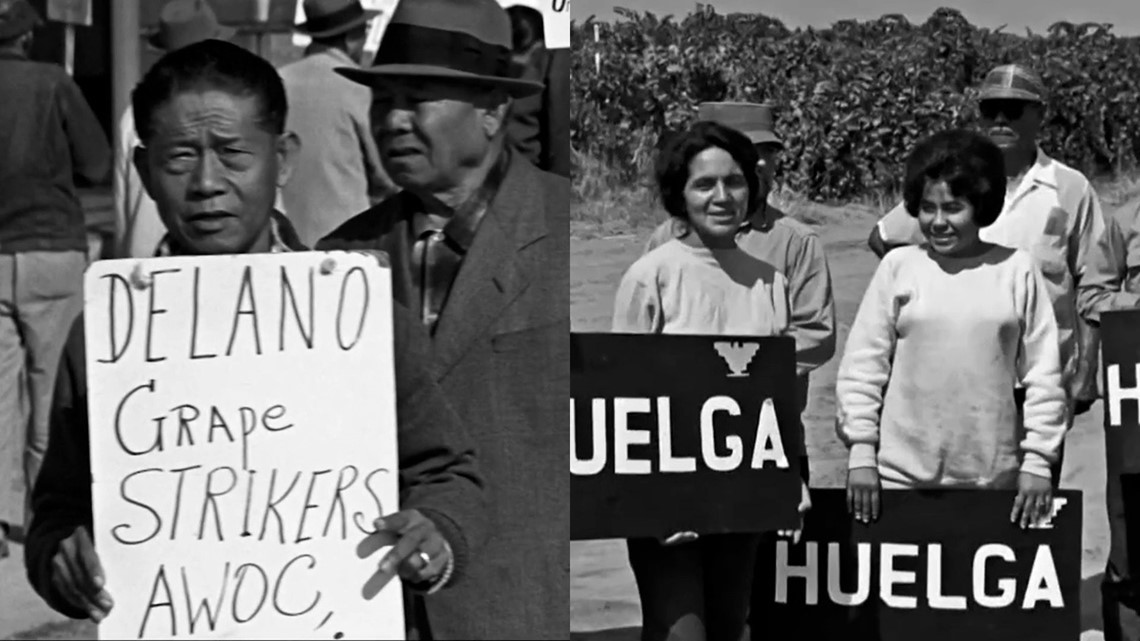

The movement began in 1965 with the launch of the great boycott in Delano, according to Lorena Marquez, a UC Davis associate professor at the Department of Chicana and Chicano studies.

The Chicano Movement was inspired by the Civil Rights Movement in the '50s and '60s, which fought for racial justice and equality for Black people.

The Delano Grape Strike and Boycott demanded better wages, education, housing and legal protections for migrant farm workers. It was initiated by Filipino farm workers organized as the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) who then invited the National Farm Workers Association, comprised of mostly Latino farm workers, to join.

“¡Si Se Puede!” — which means, “Yes, we can!” — became the rallying cry during the boycott.

In 1966, nearly 100 striking farmworkers marched from the small town of Delano to the state capitol in Sacramento.

While the 280-mile walk brought national attention to the farmworker struggle, there were many activists, organizers and everyday people who played a pivotal role in what Marquez says is a “multifaceted” movement.

There were overarching goals of the movement like ending discrimination and expanding civil and workers' rights, educational equality and land usage, but others were contingent on issues faced by location — including in Sacramento.

“Because it is an urban/rural blend, [Sacramento had] issues that many large cities were having, such as segregation, redlining, affordability, not being able to purchase homes in certain neighborhoods,” said Marquez.

For Rasul, segregation and lack of representation in the city council are what he believes helped propel the Chicano movement locally. Due to the disinvestment and negligence in his hometown, he took it upon himself to become a “community ambassador” helping people access social services and resources.

“Sacramento became the social and political hub for Chicanos and Chicanas in the area,” said Marquez.

That included the Royal Chicano Air Force (RCAF), a prominent collective of Sacramento-based artists best known for creating prints and murals pushing for social change through the 70s and 80s. Their art was an integral part of the movement helping to galvanize Mexican Americans in the fight for social justice.

GET MORE RACE & CULTURE FROM ABC10:

►Explore the Race & Culture home page

►Watch Race & Culture videos on YouTube

►Subscribe to the Race and Culture newsletter

Sacramento's role in the Chicano Movement also led to many victories.

“We had, for instance, Chicano Studies. I am absolutely a beneficiary of the Chicana/Chicano Movement. I owe my job to the movement,” said Marquez.

She also mentioned the win for cannery workers in a historic discrimination lawsuit and the creation of resource programs like College Assistance Migrant Program (CAMP) at Sacramento State that serves students from migrant and farm working backgrounds.

Rasul said that this “collective history” was not newspaper worthy at the time, but he believes it was “everyday worthy.”

He retired in 2013 but his work was not over. The same year, he was invited to join a group looking to memorialize Sacramento’s role in the Chicano movement.

The creation of the Chicano Oral History Project

Senon Valadez and Samuel “Sam” Rios are the co-founders of the Sacramento Movimiento Chicano and Mexican American Education Oral History Project.

They were graduate students of the Mexican American Education Project (MAEP) at Sacramento State College, the nation’s first master’s degree program of its kind, which was birthed out of the movement. Both went on to become professors at Sacramento State. It wasn’t until years later that they’d decide to pursue an oral history project, but not without support.

They enlisted the help of community members who participated in the Chicano Movement to be part of the steering committee.

“The first meeting I went to there was about 13 or 14 people that were interested in the project,” said Rasul.

Eventually, it dwindled down to a handful of folks. For one committee member, there was a sense of urgency to complete this project sooner rather than later.

“This really comes at a critical time as many of the early activists some 45 to 50 years ago are dying,” said Rhonda Rios-Kravitz.

To get it started, Valadez asked Lorena Marquez to direct the project. At the time, she was a lecturer for the Chicana/o Studies department at UC Davis and trained undergraduate students in her research methodology class to help conduct the interviews.

"It's a tremendous undertaking,” said Marquez. “We didn't know if we were going to be able to pull it off.”

However, in the span of a decade, her students with the help of the committee interviewed over 120 Mexican Americans. Marquez says it's the largest historical archive about the Chicano Movement in the nation. She attributes the project's success to the committee who created the interview questions as well as recruited community members.

“That's why the number is so big in terms of the interviews we were able to collect, not because of my students, not because of my role. That had to do with the fact that the committee was made up mostly of elders with the exception of myself and the videographer who are not from that generation,” said Marquez. “That's why it's a community archive. It belongs to the community and it was made up of the community.”

Rios-Kravitz was excited to pass down the history through oral storytelling.

“I think it brings history alive. It captures these personal stories and you connect with individuals really to understand their experiences and points of view,” said Rios-Kravitz.

Rasul was proud of who they highlighted; he was vocal about including a wide range of voices in the oral history project.

“We started looking at state workers, community workers that had no educational background, we looked at community members who had their heart and soul dedicated to the success of our Raza community,” said Rasul.

For those unfamiliar with the Chicano Movement, the collection may be an introduction to the involvement and contributions of Mexican Americans in Sacramento from 1965-80.

“This project is a reminder that folks have been here for a very long time. Not everyone's undocumented, not everyone has that experience,” said Marquez. “And so, this idea of otherness being a threat is a misconception. I think it's actually very dangerous for us to think of one another in that way."

Yet that idea of otherness is playing out across the country as education has become a political battleground.

In 2023, UCLA School of Law tracked legislation, letters and statements by government officials that attacked critical race theory — an academic theory developed during the 80s teaching historical patterns of racism ingrained in law and other modern institutions. In the report “Tracking the Attack on Critical Race Theory,” provided exclusively to TIME, the law school found that between Jan. 1, 2021, and Dec. 31, 2022, federal, state and local government officials introduced 563 anti-CRT measures and nearly half were enacted or adopted.

"It's really critical that we know what's happening today when we see books being banned, when we see AP classes cannot be taught, that this is a time for us, again, to showcase why we stood, why we fought,” said Rios-Kravitz. “And really, again, to speak out and say, ‘We cannot let these histories go away.’”

For Marquez, she hopes younger people who listen to these stories know they are not alone.

“I think when we see ourselves reflected in history, it empowers us to feel like we belong, that we can make a difference and that this place can be better for future generations.”

The last interviews took place in Aug. 2023. They are transcribed and available online at the Sacramento State University Library.

We want to hear from you!

The Race and Culture team's mission is to serve our diverse communities through authentic representation, community engagement and equitable reporting. Accomplishing our goals of inclusive reporting requires hearing from you. Is there a person or place that you want us to highlight? Email us at raceandculture@abc10.com or fill out the form below.