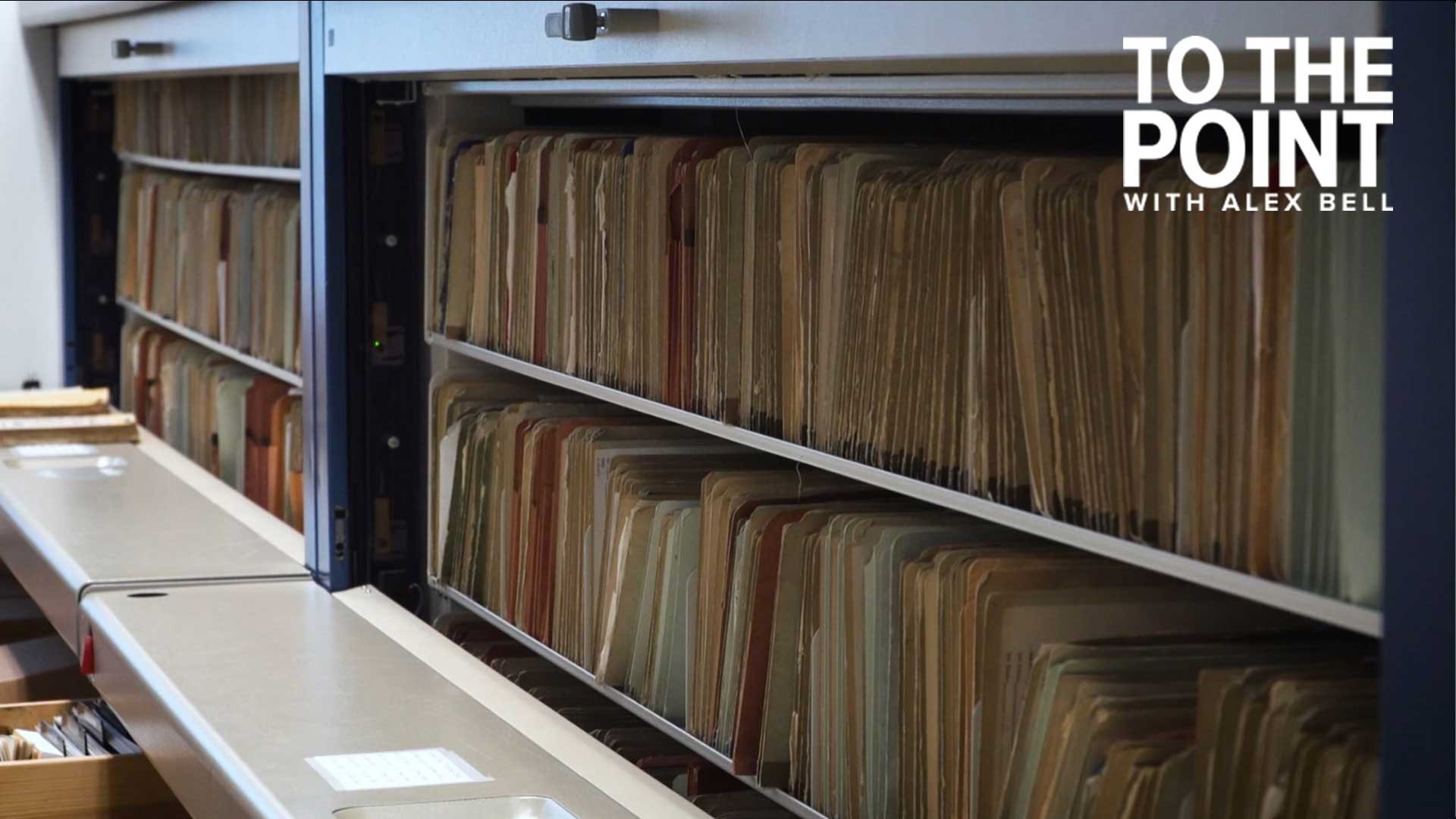

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — In the Records Room of the CalEPA building in Sacramento are some of the most important documents in the entire state of California. Some date back to 1914.

"Our files are organized in ascending order," explained Matthew Jay, an analyst with the State Water Resources Control Board. "The oldest documents are at the bottom and so you can see that some of the stuff is all typewritten and in a lot of cases, handwritten."

The papers are what's known as water rights – the backbone of life in California and its multitrillion dollar economy. Water rights are official documents validating who has the authority to take water, from where, and how much of it.

Jay works in the Records Room to keep track of all the physical water rights and their supporting documents. There are about seven million individual pieces of paper of all shapes and sizes, age and utility.

One water right contained a newspaper clipping dated November 24, 1916, with an advertisement for a new Ford Model T automobile. You could get your hands on the new 4-wheeled technology for a mere $360 if you bought the Touring Car.

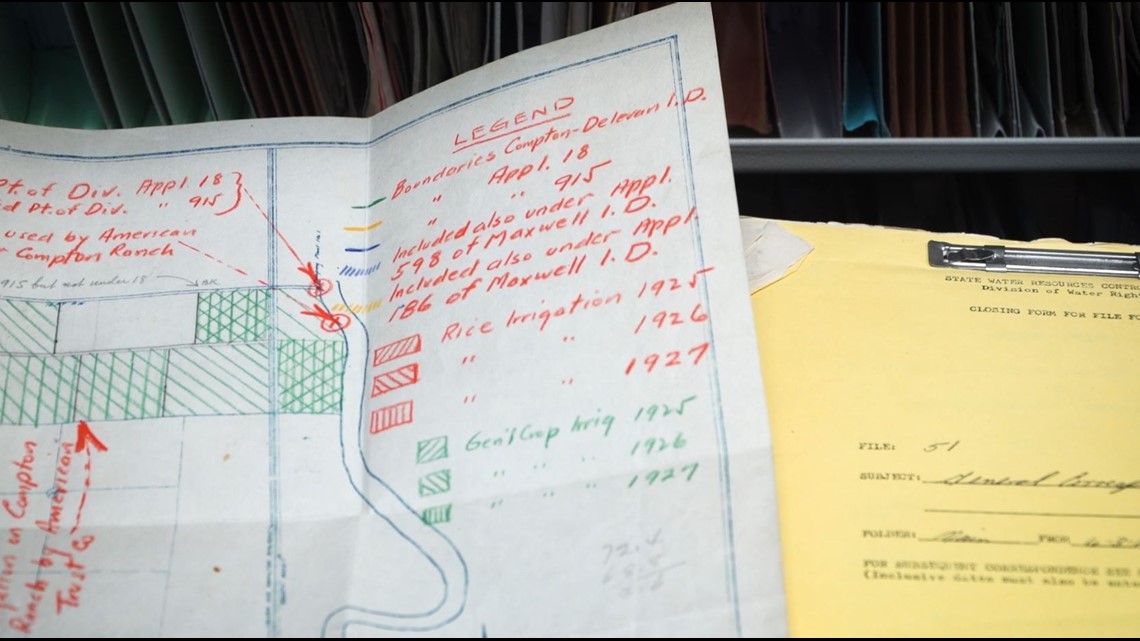

There is also an old South Bay map from the Alameda County Water District from the mid-20th century. Rubber cement was used to stitch together nine smaller maps to create one big one. Lines were hand drawn and the labels attached with rubber cement have since fallen off.

"Now it’s kind of like a puzzle piece," said Jay. "We’re trying to reach back out to these water diverters and say 'Is this up to date, is this accurate?'"

It's an important question to ask because even though some of the old surveys and maps were drawn at a time when folks were still traveling by horse and buggy, as long as the water usage hasn't been modified, they are still perfectly valid today.

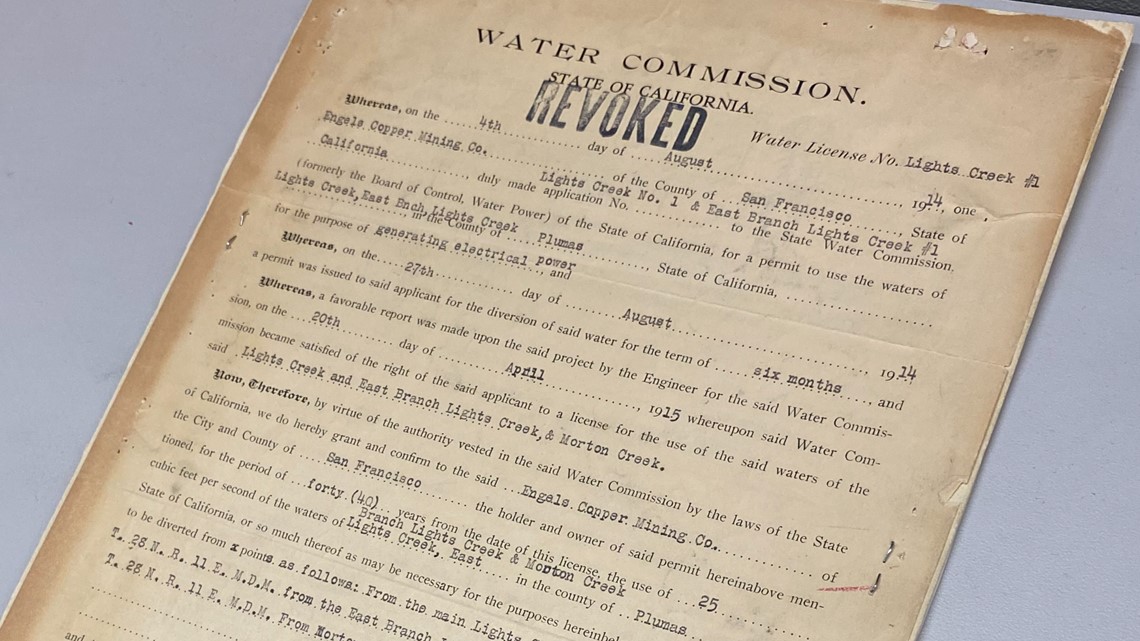

One water right no longer valid but is still significant – despite "REVOKED" being stamped across the top in bold letters – is water right #1.

Dated August 4, 1914, water right #1 was assigned to the Engels Copper Mining Company in San Francisco. It allowed them to take 25 cubic feet per second off the Lights Creek in Plumas County for 40 years.

Even though the documents and the water uses they represent are vitally important to California and everyone living in it, surprisingly, most of them are just sitting on shelves, unprotected from water, fire or other potential hazards.

The original water rights certificates – essentially just the cover sheet – for every active water right and claim in the state are sitting in one of two huge waterproof and fireproof safes.

"In case of a fire emergency or something, this actually holds the original record, the original water right license that was issued," said Jay. "So this is kind of our ancient backup plan to keep the files secure."

Yes, the backup plan to the documents governing all existing water rights – including those of the Central Valley Project and State Water Project – is a safe. If anything were to happen to the folders, binders and boxes containing the water rights and their supporting documents, all that would be left would be the certificates.

So, the natural question is: why are we still using a paper records system dating back to 1914?

"I think that we're seeing that system that was developed 100 years ago is not as fast and nimble as maybe people are expecting it given internet access, and kind of the availability of digital documents, and just the amount of information that a lot of other systems can provide," lamented Erik Ekdahl, the Deputy Director of Water Rights at the State Water Resources Control Board. "It takes us longer to do, especially when we're all based off of these paper records and kind of an antiquated approach. But for now, we implement the system that we have."

The key phrase is “for now” because work is underway to digitize the water rights. It’s a Herculean effort to digitize millions of documents of different shapes, sizes and wear. Some documents need to be shipped elsewhere to be put into a specialized scanner, yet it’s critical work not only to protect the documents from being lost but also to give the Water Board and all Californians a better understanding of what's going on in each watershed.

"Digitizing is the future," said Ekdahl. "A more robust data system that really builds into some of the modern tools will help us be more efficient, but I think it's also going to help diverters in understanding kind of what's going on in their watershed."

Understanding what goes on is the other big key to all this. Modern California water law went into effect in 1914, which is why the oldest piece of paper in the Records Room dates back that far. It's why water right #1 is dated 1914 despite there being plenty of claims prior to then.

"There were water rights that started as early as 1850, maybe even earlier," said Ekdahl. "And in fact, there are some of what we call Pueblo rights that go back into the 1700s. Only two of them, but they are there. They didn't have to apply for a permit. They didn't have to obtain a piece of paper from the board that says, 'yes, you have a water right there.'"

Prior to 1914, water rights in California were largely governed by a simple rule: first in time, first in right. Basically, if you were there first and staked a claim to the water – sometimes literally staking a sign in the ground – you had the first and most senior right to it. No bureaucracy, no surveys, no public comment period.

There's no paper trail to track and verify pre-1914 water rights grandfathered in with the passage of the 1914 water rights system.

"But there's also something called the riparian system," said Ekdahl. "Which is really, if you have land that touches a water body, you're allowed to also use that water. There's less of a first in time, first in right component to that."

Of the nearly 40,000 water rights and claims in California, roughly 18,000 – about 30% of water use in the state – are pre-1914 or riparian. It means there's no real way to track who is using what, where and how much of it in about 30% of the state.

"I don't think there's a widespread plan to undermine the water rights system," said Yvonne West, the Director of the Office of Enforcement at the State Water Resources Control Board. "I think it's a complex system with a lot of nuances, both legally and factually, and it takes some time to get acclimated to that system."

West says the majority of enforcement is not a circumstance in which someone is intentionally and willingly violating a known prohibition, however, big violations of water rights and water usage do occur.

During a drought emergency in 2022, a group of ranchers in Siskiyou County turned on their pumps and took water off the struggling Shasta River for eight days. It was so significant the streamflow dropped by more than half, threatening the long-term health of the Shasta River and its ecosystem.

The farmers were told to stop by the Water Board, but with little more than fines of $500 per day, it made more sense economically for the ranchers to keep the pumps on than it did to pay to have water trucked in. Ultimately, their penalty for overdrawing the Shasta was $4,000.

"In a situation where there is a blatant violation, intentional violation, then those are the circumstances where we would proceed with the most formal enforcement and try to maximize our ability to turn that behavior," said West. "Be it through something like a cease and desist order, or the imposition of significant administrative civil liability."

"It's really hard to use those emergency powers in the way that they're needed," said Marquis King Mason with the environmental advocacy organization California Environmental Voters.

He uses the 2022 Siskiyou County incident as an example.

"Do the math. If it's for agricultural usage, they keep getting tens of thousands of dollars from that [taking water for livestock], but they only have to pay a small amount for what was some unrepairable harm to that waterway. So, the Water Board can say, 'stop doing this,' but it takes weeks for that. It has to go through a court and has to actually be implemented," he said.

In Mason's view, the system isn't being kept up to the complexities facing the modern era.

Ekdahl and the appointed officials of the Water Board say they do the best they can with the current system.

"There are some circumstances where we've looked at financial penalties and been honestly frustrated with how much we could charge," said Ekdahl. "But that is what we're allowed to do."

Changing how the board responds, however, has to come from outside. Specifically, from the legislature.

California state senator Ben Allen is one of the people in the capitol working on the future of water. He sits on the state senate's Natural Resources and Water Committee working on water rights.

"This is precisely why we need to give more tools to the waterboard to manage the system," said Allen. "Even the people who are most vested in the status quo understand that the status quo is not sustainable."

Allen, along with state representatives Buffy Wicks and Rebecca Bauer-Kahan, California Environmental Voters and others are pushing for new legislation empowering the Water Board to make quicker, more decisive action, especially in times of drought.

"Basically, they give the Water Board more enforcement power to ensure that when we have periods of water emergency, they will have the ability to come in and fix the situation more decisively," explained Allen.

Two of the three bills failed to make it out of committee last year. While they hope to get them through this session, there’s no guarantee. The status quo, despite it being unsustainable, is difficult to change. Allen faces pushback even within his own party.

"I guess one of the questions we have to ask ourselves going forward is how do we give the Water Board the tools it needs to ensure that we've got enough water for everybody, while also respecting existing water rights so that everybody can continue to grow? And that's the challenge here," said Allen.

It's a challenge made even more difficult by climate change.

"As we see kind of climate change manifests more broadly across California, we're seeing what we call weather whiplash," said Ekdahl. "From dry to wet, and the dries are drier and hotter and more severe. So responding to that, and doing it quickly, is pretty challenging."

WATCH MORE ON ABC10: Water Wasted | What happened to all the water from California's historic winter?